รับรางวัลสูงสุดถึง 98%

ความเร็วไซต์ 100%

W88 น่าเชื่อถือไหม 100%

ฝาก – ถอนเงินที่ 100%

แอพ W88 Mobile 100%

W88 ทางเข้า W88 ล่าสุด เว็บตรง คาสิโนออนไลน์ W888

W88 เป็นเว็บไซต์การพนันสดที่ไม่ผ่านตัวแทน W888 เป็นที่นิยมอย่างมากในหมู่ผู้เล่นในประเทศไทยและเอเชีย เนื่องจากมีการเสนอผลิตภัณฑ์ที่หลากหลาย ตั้งแต่การพนันกีฬาไปจนถึงคาสิโนสด, ลอตเตอรี, เกมสล็อต และเกมอื่น ๆ อีกมากมาย ด้วยอินเตอร์เฟซเว็บไซต์ที่เรียบง่ายและใช้งานง่าย พร้อมด้วยโปรแกรมโปรโมชั่นที่น่าดึงดูด การฝาก – ถอนเงินอย่างรวดเร็ว และบริการสนับสนุนลูกค้าที่เอาใจใส่ มั่นใจได้ว่าจะนำเสนอประสบการณ์การพนันที่ยอดเยี่ยมสำหรับผู้เล่น

เกี่ยวกับ W88 – เว็บพนันตรงไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์

W88 เป็นที่ที่เล่นคาสิโนและพนันกีฬาออนไลน์ระดับชั้นนำในประเทศไทยและประเทศในแถบเอเชีย แม้ว่าเพิ่งก่อตั้งในปี 2013 แต่ W88 ก็มุ่งมั่นและพัฒนาอย่างต่อเนื่องเพื่อนำคลังเกมคุณภาพดีที่สุดมาให้ลูกค้า บริการเดิมพันที่สมบูรณ์และปลอดภัยที่สุด เมื่อเดิมพันที่ W88.com ผู้เล่นสามารถวางใจได้ W88 ได้รับใบอนุญาตให้ดำเนินการอย่างถูกกฎหมายโดย First Cagayan Leisure & Resort Corporation (CEZA) ซึ่งมีสำนักงานใหญ่ตั้งอยู่ในประเทศฟิลิปปินส์ กิจกรรมทั้งหมดของ W88 ได้ตรวจสอบอย่างใกล้ชิดโดยหน่วยงานที่มีอำนาจ เพื่อรับรองว่าเป็นสนามแข่งขันที่ยุติธรรมและโปร่งใส ไม่มีการโกงหรือฉ้อฉลผู้เล่น

ไม่เพียงเท่านั้น W888 ยังเป็นผู้สนับสนุนหลักให้กับสโมสรฟุตบอลรายใหญ่หลายแห่งในโลก เช่น สโมสร Leicester City Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C Aston Villa F.C Crystal Palace และล่าสุดคือสโมสรฟุตบอลฟูแล่ม เซ็นสัญญาแบรนด์แอมบาสเดอร์กับตำนานมากมายได้สำเร็จ เช่น Emile Heskey ในปี 2018 และ Brian Lara ในปี 2021- ซึ่งเป็นหนึ่งในนักคริกเก็ตที่ยิ่งใหญ่ที่สุดตลอดกาล สิ่งเหล่านี้ช่วยให้แบรนด์ W88 เป็นที่รู้จักมากขึ้นในหมู่ผู้เล่นและแฟนกีฬาทั่วโลก เมื่อมาที่ W88th คุณจะได้สัมผัสกับเกมที่น่าสนใจตั้งแต่การพนันกีฬา คาสิโนออนไลน์ไปจนถึงเกมสล็อต ลอตเตอรี P2P ด้วยอัตราการจ่ายเงินสูง โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ พนักงานช่วยเหลือลูกค้ามืออาชีพ และระบบการชำระเงินที่หลากหลาย การฝากและถอนเงินที่รวดเร็ว ความปลอดภัยสูง

ทางเข้า W88 ล่าสุด

เพื่อแก้ไขสถานการณ์ที่ ทางเข้า W88 ถูกผู้ให้บริการเครือข่ายบล็อกหรือ W88 เข้าระบบไม่ได้เนื่องจากมีผู้เล่นมากเกินไป W88.com อัพเดท ทางเข้า W88 ล่าสุดตลอด ดังนั้นเมื่ออยากเข้าถึงwebsite W88.com ผู้เล่นควรใช้ลิงค์ล่าสุดที่เราให้ไว้ด้านล่าง

W88 ทางเข้า มือถือ/PC ล่าสุด 2024

W88.com / m W88/ W88 Thailand / W88th / เว็บW88 / W88 มือถือ

ลิงค์สำรอง W88 เมื่อถูกบล็อก

W888 / W88ok / W88kub / W88club / WW88 / W88bkk / W88win

นี่คือทางเข้า W88 ใหม่ ล่าสุดอัปเดตเป็นประจำดังนั้นรับรองว่าไม่ถูกบล็อก ผู้เล่นสามารถเข้าถึงได้ด้วยโทรศัพท์ คอมพิวเตอร์ หรือแท็บเล็ตทุกเครื่อง… ในกรณีที่ทางเข้าW88 ถูกบล็อก ผู้เล่นสามารถใช้ลิงค์สำรองอื่นเช่น: W888, W88th, W88ok, W88kub, W88bkk, W88win,... หรือติดต่อทีมดูแลของ W88 เพื่อแก้ไขข้อผิดพลาดได้รวดเร็วที่สุด

เกมเดิมพันที่ W888

-

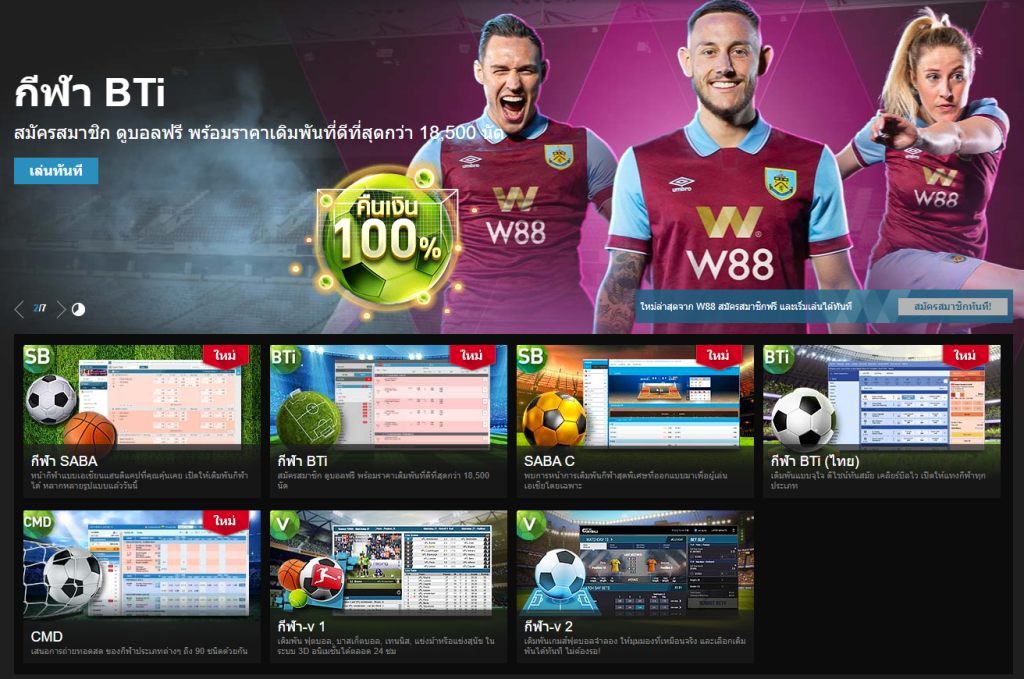

พนันกีฬา

W88 เว็บ ตรง มีกีฬาหลากหลายประเภทให้ผู้เล่นวางเดิมพัน ตั้งแต่ฟุตบอล บาสเก็ตบอล วอลเลย์บอล ไปจนถึงกีฬายอดนิยมอย่างเบสบอล คริกเก็ต เทนนิสและอีกมากมาย ภูมิใจนำเสนอการเดิมพันสำหรับทัวร์นาเมนต์ การแข่งขันกีฬาขนาดใหญ่และขนาดเล็กทั่วโลก ตั้งแต่การแข่งขันในประเทศไปจนถึงการแข่งขันระดับนานาชาติ เช่น พรีเมียร์ลีกอังกฤษ ลาลีกา กัลโช่ เซเรียอา

ที่นี่ ผู้เล่นสามารถเดิมพันเอเชียนแฮนดิแคป 1×2 สูง/ต่ำ และแทงบอลสด โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่ง W888 เสนออัตราต่อรองที่แข่งขันได้มากกว่าเจ้ามือรายอื่นและเสนอโปรโมชั่นที่น่าดึงดูดอย่างต่อเนื่อง การจ่ายเงินสูง เพื่อให้ผู้เล่นมีโอกาสเพิ่มผลกำไร

-

คาสิโนออนไลน์

W88 ถือเป็นคาสิโนออนไลน์ที่ไฮโซและหรูหรา ให้บริการเกมคาสิโนที่มีชื่อเสียงอย่างครบครัน เช่น บาคาร่า แบล็คแจ็ค รูเล็ต ซิกโบ Dragon-Tiger Poker เพื่อทำได้เช่นนี้ W88 casino ได้ร่วมมือกับผู้ให้บริการเกมคาสิโนออนไลน์ชั้นนำของโลก ลงทุนในเทคโนโลยีที่ทันสมัย วิดีโอคุณภาพสูง และเสียงที่สดใส ให้ผู้เล่นโต้ตอบโดยตรงกับดีลเลอร์ที่สวยและผู้เล่นอื่น ๆ จากทั่วทุกมุมโลก สร้างความรู้สึกที่แท้จริงเหมือนเล่นที่คาสิโนในชีวิตจริง

-

Slot game

เกมสล็อตเป็นเกมที่สนุกสนาน เล่นง่าย ชนะง่าย ดึงดูดความสนใจของผู้เล่นส่วนใหญ่ในปัจจุบัน ด้วยเหตุนี้ W88 จึงนำเสนอเกมสล็อตที่หลากหลายด้วยธีมที่แตกต่าว ตั้งแต่ธีมคลาสสิกอย่างผลไม้และเลข 7 ไปจนถึงธีมที่ซับซ้อนยิ่งขึ้น เช่น การผจญภัย มนุษย์ต่างดาวและอีกมากมาย สล็อตจากภาพยนตร์ดัง ตัวละครในตำนาน … ทั้งหมดมาจากซัพพลายเออร์ชื่อดัง เช่น Playtech, MicroGaming, Play’n Go, QTech, Evolution, PG Soft, BNG… เกมสล็อตทั้งหมดมีกราฟิกที่สวยงาม เอฟเฟกต์เสียงที่สดใส รวมคุณสมบัติที่น่าสนใจมากมาย เช่น: ฟรีสปิน แจ็คพอต ฟีเจอร์โบนัส… สัญญาว่าจะมอบประสบการณ์ที่น่าสนใจ

-

แทงหวย

หากคุณเป็นผู้ที่ชื่นชอบการพนันด้วยตัวเลข คุณไม่สามารถละเลยหมวดหวยของ W88 ได้ เว็บพนันW88 เสนอประเภทการแทงหวยที่หลากหลาย ได้แก่ คีโน ล็อตโต้ Fast 3 ตัวเลข ผู้เล่นสามารถร่วมแทงหวยไทยและหวยต่างประเทศได้มากมาย เช่น ปักกิ่ง ออสเตรเลีย แคนาดา เวียดนาม… ด้วยอินเตอร์เฟสที่เป็นมิตร อัตราการจ่ายสูง โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ การจ่ายเงินเดิมพันที่รวดเร็ว W88 ได้กลายเป็นเว็บแทงหวยออนไลน์ที่มีชื่อเสียงชั้นนำของประเทศไทย ไม่เพียงเท่านั้น W88 ยังอัปเดตผลหวยอย่างรวดเร็วและจัดเตรียมเครื่องมือทำนายผลหวยเพื่อให้ผู้เล่นสามารถตัดสินใจเดิมพันได้ดีที่สุด

-

P2P

P2P W88 เป็นสนามเดิมพันในอุดมคติสำหรับผู้ที่ชื่นชอบเกมประเภทฝึกสมอง เมื่อเข้าร่วม P2P ผู้เล่นจะแข่งขันกันเองโดยตรง แทนที่จะเผชิญหน้ากับเจ้ามือ ที่นี่ผู้เล่นจะได้สัมผัสกับเกมที่น่าสนใจเช่น: บัตรขูด, Pok Deng, Domino QQ, Gao Geo, Poker Texas Hold’em, Super Bull, Poker…. แต่ละโต๊ะเล่นออกแบบมาเป็นอาชีพ วิดีโอคุณภาพสูงและมีคำแนะนำเกี่ยวกับวิธีการเล่น เพื่อให้มือใหม่ที่ไม่มีประสบการณ์สามารถเล่นได้

แอพ W88 Mobile

W88 Mobile เป็นแอปพลิเคชั่นมือถือเฉพาะที่วิจัยและพัฒนาโดย W88 แอปพลิเคชั่นนี้ไม่มีค่าใช้จ่ายใดๆทั้งสิ้น รองรับทั้งระบบปฏิบัติการ iOS และ Android ทำให้ผู้ใช้สามารถเข้าถึงและเดิมพัน W88 ได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลา

นับตั้งแต่เปิดตัว แอพพลิเคชั่น W88 มือถือ ได้รับคะแนนสูงจากผู้ใช้งาน เนื่องจากมีข้อได้เปรียบที่โดดเด่น เช่น:

- อินเตอร์เฟสใช้งานง่าย ลื่นไหล รองรับหลายภาษารวมทั้งภาษาไทย

- รองรับเกมเดิมพันอย่างเต็มรูปแบบเหมือนเวอร์ชั่นเว็บ ได้แก่ พนันกีฬา คาสิโนออนไลน์ หวย เกมสล็อต ยิงปลา P2P…. ผู้เล่นสามารถเลือกเกมโปรดและวางเดิมพันได้ตลอดเวลา

- ตรวจสอบประวัติการเดิมพัน ประวัติการทำธุรกรรม จัดการบัญชีของคุณ และทำการฝากและถอนเงินได้อย่างง่ายดายบนโทรศัพท์ด้วยการแตะเพียงไม่กี่ครั้ง

- การสนับสนุนลูกค้าตลอด 24/7 บนแอป นโยบายความปลอดภัยสูงและอัปเดตเป็นประจำ

โปรโมชั่นของ W88 Thailand

จุดแข็งประการหนึ่งที่ทำให้ W88 ดึงดูดผู้เล่นจำนวนมากคือมีโปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจสำหรับสมาชิกใหม่และลูกค้าที่ภักดีอยู่เสมอ โปรโมชั่นบางอย่างที่ W88 Thailand ต้องพูดถึงเช่น:

- เดิมพัน เว็บพนัน W88 ทุกวัน รับโบนัสฟรีทันทีสูงถึง 250 บาท

- โบนัสต้อนรับ 100% สูงถึง 3,000 บาท สำหรับสมาชิกใหม่เมื่อเข้าร่วม A-E-X- Sports Live Casino Keno ของ W88 คาสิโนออนไลน์

- โบนัสต้อนรับสมาชิกใหม่ 20% เมื่อเข้าร่วมทุกเกมเดิมพันของ W88 ด้วยมูลค่าโบนัสสูงสุดถึง 6,000 บาท

- รับโบนัสต้อนรับ 100% สูงสุด 6,000 บาท เมื่อสมัครเกมสล็อต W88

- โบนัสเงินฝากครั้งแรก 10% ที่ A-Sports สูงถึง 1,500 บาท และ e-sports สูงถึง 3,000 บาท 20% ที่ X-Sport สูงถึง 1,000 บาท

- เงินคืนสูงถึง 0.2% ที่ A/X- Sports และ 0.3% ที่ E-Sports

- เงินคืนสูงถึง 0.8% สำหรับเกมคาสิโนออนไลน์ และ 1% สำหรับเกมสล็อต W888 อัตราการคืนเงินจะขึ้นอยู่กับระดับของสมาชิก

ฝาก – ถอนเงินที่ W88th

W88Thai มีระบบการชำระเงินที่รวดเร็ว หลากหลาย และปลอดภัย ทำให้ผู้เล่นสามารถฝากและถอนเงินได้อย่างยืดหยุ่น โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่ง ผู้เล่นสามารถเลือกวิธีการชำระเงินดังต่อไปนี้: การโอนเงินผ่านธนาคาร การชำระเงินผ่าน Quickpay FastPay WPay Neteller e-wallet เป็นต้น ด้วยระยะเวลาการดำเนินการของธุรกรรมการฝากเพียง 5-10 นาที การถอนเงินภายใน 30 นาที นอกจากนี้ W88Thailand ยังไม่เก็บค่าธรรมเนียมการฝาก/ถอนจากผู้เล่น ผู้เล่นสามารถทำธุรกรรมได้ตลอดด้วยระบบประมวลผลการฝากและถอนอัตโนมัติ W88 ยังร่วมมือกับธนาคารหลักส่วนใหญ่ในประเทศไทย: กรุงไทย สยาม กรุงเทพ… เพื่อสนับสนุนผู้เล่นอย่างดีที่สุด มุ่งมั่นที่จะรักษาความลับของข้อมูลบัญชีลูกค้าและข้อมูลการทำธุรกรรม

ทำไมต้องเลือกเว็บพนัน W88

สำหรับผู้ที่เดิมพันมาเป็นเวลานาน คุณคงคุ้นเคยกับชื่อ W88 อย่างแน่นอน แต่สำหรับผู้เล่นใหม่ก็ยังมีข้อกังวลมากมาย ดังนั้นในเนื้อหาถัดไป เราจะแบ่งปันกับผู้เล่นถึงข้อได้เปรียบที่โดดเด่นของ เว็บพนัน W88:

- W88 เป็นเจ้ามือที่ได้รับอนุญาตให้ดำเนินการอย่างถูกกฎหมายโดยองค์กรที่มีชื่อเสียงในโลก มีศักยภาพทางการเงินที่แข็งแกร่งและเป็นผู้สนับสนุนสโมสรฟุตบอลที่มีชื่อเสียงหลายแห่ง

- เว็บพนันW88 มีเกมพนันยอดนิยมมากมายให้ผู้เล่นได้เลือก รวมทั้ง: พนันกีฬา คาสิโนออนไลน์ เกมสล็อต ยิงปลา หวย P2P…

- ส่วนต่อประสานเว็บไซต์ที่เป็นมิตรกับผู้ใช้ รูปภาพคุณภาพสูง เลย์เอาท์จัดวางทางวิทยาศาสตร์ ช่วยให้ผู้ใช้ค้นหาและเข้าร่วมเกมโปรดได้อย่างง่ายดาย

- รองรับวิธีการชำระเงินที่ปลอดภัยมากมาย เวลาดำเนินการที่รวดเร็วสำหรับการฝากและถอนเงิน

- เว็บW88 เสนอโปรโมชั่นอย่างสม่ำเสมอสำหรับผู้เข้าร่วมใหม่และผู้ใช้เดิม เช่น โบนัสต้อนรับ โบนัสเงินฝากครั้งแรก เงินคืนเมื่อแพ้เดิมพัน เป็นต้น

- W88 เว็บตรง มีชื่อเสียงในด้านการบริการลูกค้าอย่างมืออาชีพที่พร้อมตอบคำถามของผู้ใช้ผ่านช่องทางต่างๆ มากมาย เช่น แชทสดบนเว็บไซต์ อีเมล hotline…

- นโยบายการรักษาความลับของข้อมูลมีความปลอดภัยอย่างเด็ดขาด โดยใช้มาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยขั้นสูงเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลและบัญชีผู้ใช้

คู่มือเข้าร่วมเดิมพันที่ W88.com

ในการเข้าร่วมเดิมพันที่ W88 นั้นง่ายมาก ผู้เล่นเพียงแค่ทำตามคำแนะนำดังต่อไปนี้:

- ขั้นตอนที่ 1: สมัครบัญชี W88

เข้าสู่เว็บไซต์ W88 ผ่านลิงค์อย่างเป็นทางการที่เราให้ไว้ด้านบน คลิกที่ปุ่ม “สมัคร” ที่มุมขวาของหน้าจอ กรอกข้อมูลส่วนตัวของคุณตามที่ระบบขอ => คลิกยืนยันเพื่อเสร็จสิ้นขั้นตอนการสมัคร W88

- ขั้นตอนที่ 2: ฝากเงินเข้าบัญชี W88

หลังจากลงทะเบียนบัญชีสำเร็จ คุณต้องฝากเงินเข้าบัญชี W88 ของคุณเพื่อให้สามารถเข้าร่วมเดิมพันได้ที่นี่ W88เว็บตรง รองรับวิธีการชำระเงินที่หลากหลาย คุณเพียงแค่ต้องเลือกวิธีที่เหมาะสมและทำตามคำแนะนำ

- ขั้นตอนที่ 3: เข้าร่วมเดิมพัน

เลือกผลิตภัณฑ์การเดิมพันที่คุณต้องการเข้าร่วมและวางเดิมพันตามคำแนะนำ W888 เสนอความบันเทิงประเภทต่างๆ มากมาย เช่น พนันกีฬา คาสิโนออนไลน์ เกมสล็อต ยิงปลา หวย… แต่ละเกมมีเวอร์ชันทดลองให้เล่นก่อน

- ขั้นตอนที่ 4: ถอนเงินที่ชนะ

หลังจากที่คุณชนะการเดิมพัน คุณสามารถถอนเงินไปยังบัญชีส่วนตัวโดยใช้วิธีการชำระเงินที่ W88 Thai จัดให้ อย่างไรก็ตาม ก่อนทำธุรกรรม คุณต้องตรวจสอบว่าโบนัสโปรโมชั่นตรงตามเงื่อนไขของ W88 หรือไม่

สรุป

โดยทั่วไปสามารถยืนยันได้ว่า W88 เป็นหนึ่งในเว็บพนันออนไลน์ที่มีคุณภาพและมีชื่อเสียงและได้รับเลือกจากผู้เล่นจำนวนมากในปัจจุบัน ด้วยข้อได้เปรียบที่โดดเด่นมากมาย เช่น ผลิตภัณฑ์การเดิมพันที่หลากหลาย โปรโมชั่นที่น่าสนใจ การบริการลูกค้าอย่างมืออาชีพ นโยบายความเป็นส่วนตัวที่ปลอดภัย และวิธีการชำระเงินที่สะดวกมากมาย W88th สัญญาว่าจะเป็นจุดหมายปลายทางในอุดมคติที่นักพนันไม่ควรพลาด

FAQ

ฉันสามารถลงทะเบียนที่ W88 ได้กี่บัญชี

ตามข้อกำหนดของ W888 ผู้ใช้แต่ละคนได้รับอนุญาตให้ลงทะเบียนและเป็นเจ้าของบัญชีเดียวเท่านั้น วัตถุประสงค์ของกฎระเบียบนี้คือเพื่อความยุติธรรมและหลีกเลี่ยงการฉ้อโกงหรือการใช้ข้อเสนอและการส่งเสริมการขายในทางที่ผิด

หาก W88 ตรวจพบว่าผู้ใช้จงใจลงทะเบียนหลายบัญชี ระบบจะบล็อกบัญชีทั้งหมดและไม่อนุญาตให้ผู้ใช้เดิมพันหรือถอนเงินจากบัญชี

W88 น่าเชื่อถือไหม

W88 ได้รับใบอนุญาตจากองค์กรรัฐบาล First Cagayan Leisure & Resort Corporation (CEZA) ซึ่งมีสำนักงานใหญ่ในฟิลิปปินส์ กิจกรรมทั้งหมดของ W88.com ได้ตรวจสอบอย่างใกล้ชิดโดยหน่วยงานที่มีอำนาจ เพื่อรับรองว่ามีสนามแข่งขันที่โปร่งใส ยุติธรรม และปลอดภัย

ไม่เพียงเท่านั้น W888 ยังเป็นผู้สนับสนุนหลักให้กับสโมสรฟุตบอลที่มีชื่อเสียงระดับโลก นโยบายความปลอดภัยของข้อมูลยังถูก W88 ให้ความสำคัญเป็นอย่างยิ่งโดยใช้มาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยขั้นสูงเพื่อปกป้องข้อมูลส่วนบุคคลและข้อมูลบัญชีของผู้ใช้

จากข้อมูลข้างต้น เราสามารถยืนยันได้อย่างมั่นใจว่า W88th เป็นเจ้ามือที่มีชื่อเสียงและเชื่อถือได้สำหรับคุณในการเข้าร่วมการพนันออนไลน์

แอพ W88 Mobile เสียค่าใช้จ่ายไหม

การดาวน์โหลดและใช้งานแอป W88 Mobile นั้นฟรีทั้งหมด จุดประสงค์ของแอป W88 คือการสร้างเงื่อนไขที่เอื้ออำนวยให้ผู้เล่นสามารถเข้าร่วมในเกมเดิมพันได้ทุกที่ทุกเวลาบนโทรศัพท์ ผู้เล่นสามารถดาวน์โหลดแอปได้โดยตรงจากเว็บไซต์ W88 หรือค้นหาในแอปพลิเคชัน Google Play Store และ App Store

ข้อมูลส่วนตัวที่ W88 ปลอดภัยหรือไม่

W88 มุ่งมั่นที่จะรักษาข้อมูลลูกค้าให้ปลอดภัย รวมถึง: ข้อมูลส่วนบุคคล ข้อมูลบัญชี ธุรกรรมการฝาก-ถอนเงินของผู้เล่น… เพื่อทำได้เช่นนั้น W88 ใช้มาตรการรักษาความปลอดภัยที่ทันสมัยที่สุดในปัจจุบัน เช่น เทคโนโลยีความปลอดภัย SSL 128 บิต ข้อมูลที่ผู้ใช้ให้ทั้งหมดจะถูกเข้ารหัสและป้องกันในสภาพแวดล้อมที่ปลอดภัย W888 ไม่เปิดเผยข้อมูลลูกค้าแก่บุคคลที่สาม เว้นแต่จะได้รับคำสั่งจากศาลหรือได้รับความยินยอมจากผู้เล่น